Mary is still using the BiPap/AVAPS (non-invasive ventilator) 24/7 in order to breathe, and a Cough Assist machine to help keep her lungs clear since her respiratory muscles are so weak (her NIF is -8; normal is -80).

She had a feeding tube (PEG) placed on April 2 proactively; at the time she did not need it as she was still eating normally, but we were concerned that her impaired breathing would make anesthesia more dangerous if we waited. In the past couple of weeks, she has had some occasions where she has aspirated small pieces of food (which the Cough Assist was able to clear), so we are looking at changing her diet to more of a soft food and liquid diet, and beginning to use formula in her feeding tube. She has also lost a total of 45 pounds since last summer, so she is on a high-carb, high -protein diet.

Her left side has continued to atrophy and she is no longer able to walk on her own or stand for more than a few seconds. She is wearing a neck brace 24/7 to keep her head upright and minimize the trigeminal nerve pain that she gets due to the muscle loss in her back, neck and head. She is using power wheelchair to get around, and we use a lift to transfer her into bed at night since she cannot get into our current bed. We are waiting for an adjustable bed to be delivered, that we hope will help her sleep better, since she also can’t reposition herself in bed.

We currently have home health services about 40 hours a week, and she is being reassessed tomorrow in the hopes that we can get additional home health services. We have had some issues with some of the caregivers and visiting nurses, and have had to fight to make some personnel changes, but we are hopeful that the current professionals will work out longer term.

She isn’t able to leave home unless a wheelchair van can come and get her. When my parents were here two weeks ago I was able to rent a wheelchair van for a couple of days. We made a trip to a local nursery and then a trip to the Evergreen Air and Space Museum with my parents. Not having easy transportation access is the one drawback of living so far out in the country.

We have been blessed by visits from Callista and Allejandro and Elfkat. We are looking forward to a visit from Elfkat and Diana over the Fourth of July weekend.

Despite the rapid changes and challenges and questions and decisions the future holds, Mary is doing her best to stay in a positive frame of mind. She is enjoying watching the hummingbirds come to the feeder outside the living room window, and gets outside when the weather permits (and chases the caregivers were around with her wheelchair!). She is looking forward to the fresh foods from our garden (planting is an ongoing project since I have minimal time to spend in the garden).

Please continue to send Reiki, positive energy and thoughts for both of us. And if you are so inclined, please support the ALS Association in bringing awareness and helping to find a treatment and someday a cure.

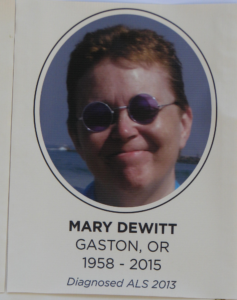

een 19 months since Mary crossed to the Summerlands. I promised her that when she was done fighting, I would fight for everyone else. This months’ posts have been one way I continue to do that.

een 19 months since Mary crossed to the Summerlands. I promised her that when she was done fighting, I would fight for everyone else. This months’ posts have been one way I continue to do that.